More than 5 million Canadians do not have access to a reliable source of clean drinking water. Many living in rural or First Nations communities.

Nearly 20% of Canada’s First Nations live with compromised drinking water

Around 37.7 million people are affected by waterborne diseases in India

There are about 2.5 billion people worldwide who do not have access to clean, potable water. Nearly 6 million Canadians in small, rural, and aboriginal communities; and close to 504 million people who reside in rural India are amongst the underserved dwellers.

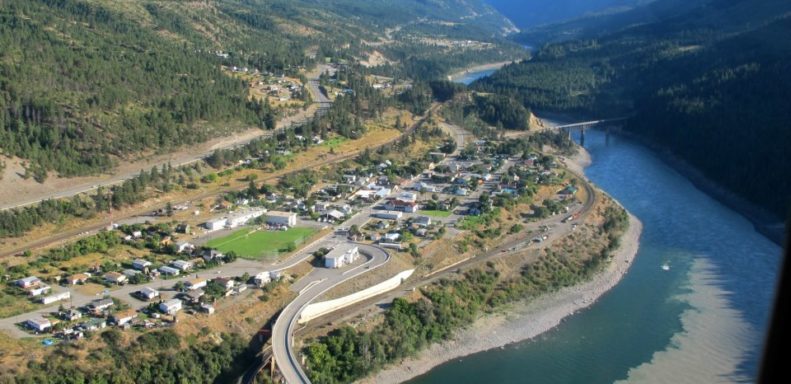

Lytton in British Columbia, Canada, sits at the confluence of the Thompson River and Fraser River on the east side of the Fraser. The location has been inhabited by the Nlaka’pamux First Nations people for over 10,000 years. Surrounded by magnificently diverse mountain ranges, the Village of Lytton is 260 km northeast of Vancouver along the Trans-Canada Highway. Lytton is one of the earliest locations settled by non-natives in the Southern Interior of British Columbia, having been founded during the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush of 1858–59, when it was originally known as “The Forks”.

The population of the village municipality as of the 2011 census was 228, with another 1,700 in the immediate area living in rural areas and on reserves of the neighboring six Nlaka’pamux communities.

Two or three times a year, when the snow melts or the rain comes, a boil water advisory is issued to the Lytton community. For some homes, the advisory is never lifted – their drinking water constantly tests high in bacteria and positive for E. coli. At the end of February 2016, 26 communities in B.C. were under boil water advisories — some of them dating back 10 years. “The issue and the challenge is that even though that water comes from pristine sources, some of those sources are susceptible to microbial contamination,” UBC engineering professor Madjid Mohseni explained.

“Those communities are often very remote … much of the funding needs to be paid by the ratepayers or the users, and when you have only tens of people living there, it’s very difficult for them to afford installing a treatment system.”

Dr. Mohseni explained, “many of B.C.’s 3,000 water systems are in small, remote communities with limited resources. For them to finance a water treatment system that is going to provide consistent, good quality water, it is going to cost a lot of money per household. Some really simply don’t have the capacity to make any progress.”

The Res’eau water treatment system’s services at Lytton Village will provide potable water to 6 homes from the source water from Nickeyeah Creek.

During our pilot work … the operators got the necessary hands-on training and were able to establish whether they could operate the system”

Dr. Madjid Mohseni, Chemical and Biological Engineering Professor, University of British Columbia

The installed water treatment system provides our community with excellent drinking water so they no longer have to buy it from other sources”

Jim Brown, Lytton First Nations operations manager

Along with technical expertise, the project involves what it calls a “community circle approach” – working with communities to determine technical requirements and local capacity to maintain and run a new system. “The Lytton First Nation had previously been quoted a price of more than $1 million to upgrade its water treatment facilities. The Res’eau treatment system was implemented for less than half that, including research costs”, Dr. Mohseni said.

“It was great to work with the mobile unit, because you really don’t know what is going to work until you try it,” Brown said. “We put the water through the different processes and determined what was best for our water quality.” The upside for the community is the relatively low cost. The mobile water treatment micro-plants developed, consist of a variety of filtration and purification modules, including different sized filters, an ion exchanger, activated carbon for off-taste and smell, ultraviolet (UV) purifiers and a chlorination system.

Second-generation prototypes of the passive membrane system will be ready for field-testing soon. The new prototypes incorporate the knowledge gained as part of recent IC IMPACTS research, and are much simpler, both mechanically and operationally. The operation of the prototypes can also be either manual (when no/limited electrical power is available) or automated.

2024 IC-IMPACTS Conference in Delhi December 9 - 11, 2024 New Delhi, India